A scholar of Black Consciousness, Thegatvolblogger, studying I Write What I Like which provides an exposition of Steve Bantu Biko’s Black Consciousness Philosophy.

I Write What I Like is a book featuring the collection of articles written by Steve Bantu Biko. It is an exposition of the Black Consciousness Philosophy. The book’s title comes from the heading of the column in which Biko published his articles in the SASO [South African Student’s Organisation] newsletter. These articles written using his pseudonym Frank Talk form the core of the book.

I Write What I Like also comprises addresses, letters, reports and interviews he gave during the formation of SASO in 1969 until months before his death in 1977.

This collection was published in 1978 a year after his death. Aelred Stubbs edited the collection and also wrote the preface.

The series of articles, fifteen in total plus four extras, that form I Write What I Like are supplemented by two transcripts from Biko’s evidence in the SASO/ BPC Trial that took place in the first week of May 1976; an interview conducted by a European journalist in the first half of 1977 and an extract from an interview conducted by an American businessman month’s before Biko’s final detention and death.

The extras in the book are What is Black Consciousness; The Righteousness of our Strength, Our Strategy for Liberation and On Death. In total, there are 19 chapters in this collection that set out the Black Consciousness Philosophy in Biko’s own words.

The video below is the first part of the interview which appears in Chapter 18 of I Write What I Like: it is entitled Our Strategy for Liberation although the video title states Steve Biko Speaks on the Black Consciousness Movement.

The complete video which is in three parts is a recapitulation of the whole argument or exposition of Black Consciousness collected in this book.

He reflects on the impact of the student uprisings in Soweto and elsewhere in South Africa since June 1976, and lays out his plan for a united liberation front to confront the forces of oppression.

It is here that he explains his vision and unique mission to reconcile the African National Congress [ANC] and Pan African Congress [PAC] and bring them into this united liberation front. At this point he is still hoping for a non-violent solution to stem the rising racial conflict.

I first encountered Biko through fleeting media reports as I was growing up. There was an aura about him that struck a lasting impression on me then but I was way too young then to understand his significance and relevance.

I understood then as I know now that he was unjustly killed by white policemen. Over the years I gathered fragments here and there that put more perspective to this face that was embedded in my subconscious.

It was only when I stumbled on the movie Cry Freedom, the powerful film produced and directed by Richard Attenborough featuring Denzel Washington as Biko, that I began to gain a better understanding of his significance and legacy.

The book Biko written by Donald Woods, former editor of the Daily Dispatch and a personal friend of Biko, introduced me to the Black Consciousness Philosophy.

The book contained quotes and extracts from Biko’s article which gave me a deeper appreciation of the finer nuances about the Black Consciousness Philosophy.

It wet my appetite and I hungered to feed myself from from the source. Both the movie and the book transformed me into a convert and set me off on my quest to read more about Biko until I discovered I Write What I Like. That was my conversion.

Since then I have read the book numerous times. With each subsequent reading, I always discover something I missed during the previous reading.

The book is so well written, any reader, reviewer or critic is spoilt for quotes which is a testimony to the quality of its content and ideological relevance. That is the hallmark of a good writer. Each time I read the text I wish I had written those lines.

My first experience of engaging with the writing of Biko was like discovering an oasis of freedom in a desert of enslavement. His work is on the same par as the writing of Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, the speeches of Thomas Sankara and the Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Humanity would be much impoverished if we were robbed of the work of these prophet intellectuals and philosophical giants.

My only criticism of the book is that it is too short and left me wanting more which is a good thing.

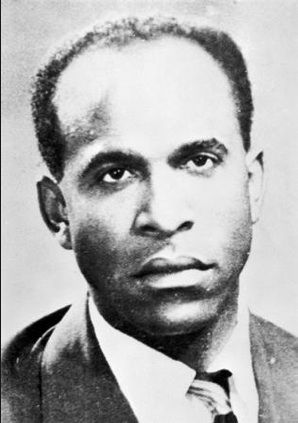

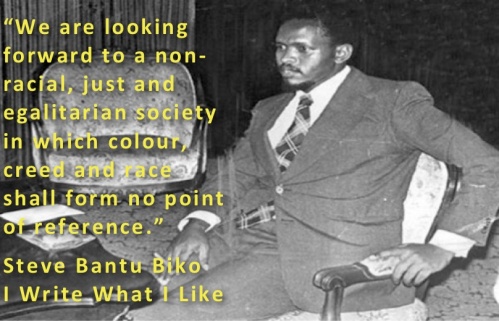

Steve Biko, or Bantu as he was popularly known among his own people in Ginsberg [King William’s Town], was the legendary anti-apartheid activist, dissident or public intellectual and Black Consciousness philosopher.

Bantu was the name he was given by his parents when he was born on the 18th of December 1946 in King William’s Town. Bantu means people.

It was an apt name, a premonition, a precursor of his abilities or God given gift to reach out and connect with old and young people and others of all races. I Write What I Like reflects this quality of Biko.

He was the co-founder of SASO, the Black Consciousness Movement and the Black Community Programmes which set up community programmes like the Ginsberg Crèche, Ginsberg Educational Fund, Njwaxa Home Industries, Zimele Trust Fund [established to help black political prisoners and their families] and Zanempilo Health Clinic.

I Write What I Like reinforces Biko’s belief that the liberation and salvation of Black people in South Africa lies in their own hands. It will come about when they operate as a unified group. It is only through the liberation of their minds that they can break their shackles of subjugation.

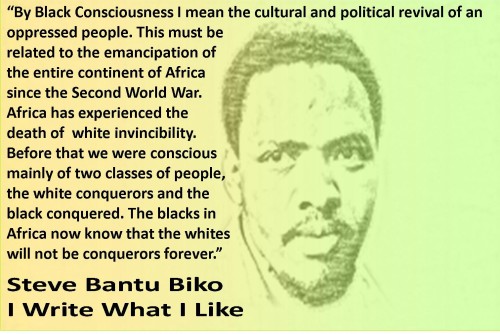

Black Consciousness is his special inspiration, the unwavering belief that the Black is as equal and as worthy as any other. This is not mere grounds for recrimination. Far from it.

He wishes the Black man and woman has the same rights as others and that they must fearlessly claim them. Freedom and liberty means personal responsibility which is important to pursue, even unto death, or compromise full personhood.

These are his beacons, cardinal points, goalposts and references points. These form his guide. These are some of the key tenets of the Black Consciousness Philosophy and the movement of which he was a co-founder.

There are recurring themes in I Write What I Like. These are Blackness; consciousness, fear, freedom, liberals, liberation, oppression, power, racism, subjugation. These themes are interwoven within the series of articles to form the Black Consciousness philosophy.

Biko’s intention is to conscientise Black people to grapple realistically with their problems, to attempt to find solutions to their problems, to develop what one might call an awareness of their situation, to be able to analyse it, and to provide answers for themselves.

For Biko, “Black Consciousness is a way of life, the most positive call to come out of the black world for a long time”. It is not hyperbole. It is not political rhetoric.

It is revolutionary. It is the future. It is the vehicle that transforms the attitudes and thinking of generations to come. It is revolutionary because it rejects the old approach, old slogans, protests, and meaningless rhetoric of previous years in the struggle against apartheid.

The language of yesteryear is dead. Buried. Terms like coalition, fear of white policemen or the government, integration, protests, etc. are remnants of a bygone era.

The door is shut in the face of white integrationists. The ranks are closed. Black students, on the other hand, begin to rethink their position in Black-white coalitions.

There emerges in South Africa a group of angry young black men who are beginning to grasp the notion of their particular uniqueness and who are eager to define who they are and what.

The emergence of SASO and its tough policy of non involvement with the white world sets people’s minds thinking along new lines.

It is a challenge to the age-old tradition in South Africa that opposition to apartheid is enough to qualify whites for acceptance by the Black world.

Biko is at the forefront of this radical thinking. He is one of the key thinkers and strategists. He is not a mere theorist but a man of action.

He helps set up organisations rooted in oppressed communities, promoting self-reliance projects that affirm that blacks should earn their own keep with dignity while taking care of one another.

They should reassess how they use their economic, cultural, social and political capital, and reinvest it within their own communities to uplift themselves.

The myth of the invincibility of the white man is exposed. His white yardstick of values and beliefs is discarded like an ill fitting garment. The masquerade of apartheid is unmasked and the vanity exposed and challenged.

The Black Consciousness Movement re-shapes the struggle terrain and redefines the rules and terms of engagement. Their focus shifts from the periphery and they begin an in-looking process that focuses on the mind of the oppressed because they realise that it is the most powerful weapon in the arsenal of the oppressor.

The book covers the philosophy of Black Consciousness. It addresses crucial and diverse issues such as African culture, apartheid, bantustans, Black liberation, capitalism, the Christian church, economic exploitation, white liberals, white racism, and Western support for the apartheid regime, etc.

I Write What I Like captures Biko’s charisma, intellect and vision. It portrays an astute philosopher rooted at the center of the struggle for freedom, setting out his idyllic road map to a new society.

Philosophy is not a term normally associated with or attributed to Biko. He’s primarily viewed through the prism of a political activist, dissident or public intellectual and overshadowed by the looming shadow of his tragic death.

In layman terms, a philosopher is a person who studies philosophy, or a person who remains calm and stoical in the face of difficulties or disappointments. Both definitions are Biko personified.

Numerous writers such as Father Alered Stubbs, Donald Woods – Biko, Barney Pityana and Xolela Mangcu – Biko A Life who were personally acquainted with the legend bear testimony to Biko’s character as someone who remained calm and stoical in the face of difficulties or disappointment.

The book is a wealth of history, philosophy and psychological insight, understanding, wisdom and wit. Biko was an avid reader and the book reflects his engagement with the philosophical writings of Jean Paul Sartre, Karl Jaspers, Aime Cesaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Stokely Carmichael a.k.a. Kwame Ture, Frantz Fanon, etc.

I Write What I Like contains references, quotes, allusions, approaches, ideas or methodologies similar to the intellectuals mentioned above.

This is an illustration of his intellectual fluidity. The references to their philosophies or thoughts suggests Biko’s mind is a multiplicity of selves. Understanding those selves implies understanding others and society in general.

Most voracious or widely read readers are able to learn twice as fast because they have the ability to learn through the experiences and lessons that took others a lifetime to understand and articulate as coherent truths.

Some of these allusions, approaches, ideas, references and methodological similarities are evident.

For example, Carmichael and Hamilton Define Black Power in 1967 state, “The adoption of the concept of Black Power is one of the most legitimate and healthy developments in American politics and race relations in our time“.

In contrast, Biko writes in White Racism and Black Consciousness, “The call for Black Consciousness is the most positive call to come from any group in the black world for a long time”.

There are differences in the contexts, diction and semantics but the similarities in defining themselves is evident. However, it doesn’t end there.

Carmichael and Hamilton state, “Black Power therefore calls for black people to consolidate behind their own, so that they can bargain from a position of strength”.

“Before black people join the open society, they should first close their ranks, to form themselves into a solid group to oppose the definite racism that is meted out by the white society, to work out their direction clearly and bargain from a position of strength,” Biko writes in comparison.

The Black Power Movement state “Black visibility is not Black Power”. Biko and SASO on the hand say, “What we want is not black visibility but real black participation”.

It is evident the Black Power Movement and the Black Consciousness Movement share similar ideas and strategies. The two movements are like ideological twins.

They are willing to walk on a tightrope. They refuse to conform to external expectations. They dare to invent the future like mad men.

Their thinking is on a deeper level. They question power. They question values. They question identities, the system and everything.

Their focus is not merely on external decolonisation but on the decolonisation of the mind which Biko refers to as an inwards looking process.

Stokely Carmichael with his wife, South African musician, Miriam Makeba shortly before they left America to live in Guinea, Africa.

There are also similarities in their strategies such as the exclusion of liberals, calls for organisation, calls to reject racist institutions, define their own goals, lead their own organisations and support their own organisations.

They are kindred spirits who have never met but are like liberation twins who are separated at birth but still think alike though they are thousands of miles apart. Though their paths never cross, but the roads they travel are similar.

The following quotation from the Black Power Movement [Carmichael and Hamilton] wouldn’t be out of place in I Write What I Like:

“The point is obvious: black people must lead and run their own organizations. Only black people can convey the revolutionary idea – and it is a revolutionary idea – that black people are able to do things themselves. Only they can help create in the community an aroused and continuing black consciousness that will provide the basis for political strength. In the past, white allies have often furthered white supremacy without the whites involved realizing it, or even wanting to do so. Black people must come together and do things for themselves. They must achieve self-identity and self-determination in order to have their daily needs met. . . “

Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement and the Black Power Movement in America have similar ideas and approaches although they are operating in different contexts. This is probably due to the similarities of their struggles.

They are both fighting against a capitalist system where white capital and racism identify the black skin as a mark of subservience; therefore, subjects to be subjugated and economically exploited for the benefit of the white population.

Biko believes that the Black people of the world, in choosing to reject the legacy of colonialism and white domination and to build around themselves their own values, standards and outlook to life, are establishing a solid base for meaningful cooperation among themselves in the larger battle of the Third World against the rich nations.

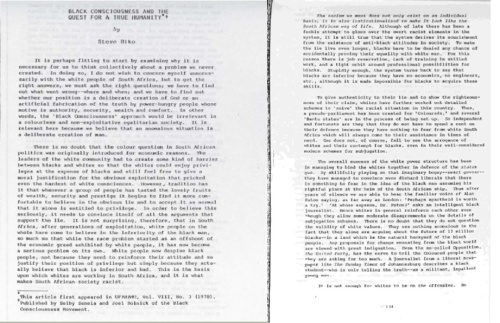

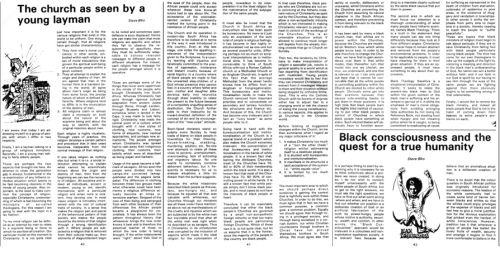

In the essay, Black Consciousness & the Quest for a True Humanity, illustrated in the image of the excerpt below, it illustrates Biko’s understanding of different disciplines resulting from his wide reading.

The link above links to a PDF version of this article that you can read online. Many argue that this is one of Steve Biko’s most articulate articles and the best he ever wrote.

An excerpt from the article Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity written by Steve Biko and taken from the book I Write What I Like.

This article addresses the points I raised above. It goes further to pinpoint the role of the church in the subjugation and exploitation of Black people through creating a just cause condoning the oppression of Black People.

Biko believes the Black Consciousness approach would be irrelevant in a colourless and non-exploitative society. It is relevant here because the anomalous situation is a deliberate creation of man.

“The leaders of the white community had to create some kind of barrier between blacks and whites so that the whites could enjoy privileges at the expense of blacks and still feel free to give a moral justification for the obvious exploitation that pricked even the hardest of white consciences,” he writes.

It is worth reading further to understand how and why these barriers were created, and the role the missionaries played although they knew that not everything they were doing was necessary to spread the word of God.

One of the greatest influences on Biko’s Black Consciousness Philosophy is Frantz Fanon. Fanon’s works such as Black Skin, White Masks inspired some of Biko’s articles like Black Souls in White Skins, White Racism and Black Consciousness and Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity.

The Martinique-born Afro-French psychiatrist, philosopher, revolutionary, and writer, Frantz Fanon, who wrote books like The Wretched of the Earth and Black Skin, White Masks had a major influence on the writing and thinking of Steve Bantu Biko.

At times Biko paraphrases Fanon. At times he acknowledges his contribution through direct quotes; e.g. he quotes him directly in White Racism and Black Consciousness:

As Fanon puts it: “Colonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content; by a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of the oppressed people and distorts, disfigures, and destroys it.”

As pointed out above, “emptying the native’s brain of all form and content” and distorting, disfiguring and destroying of the past was the modus operandi of the missionary and his brainwashed education and religion.

Biko is not content to merely paraphrase or quote Fanon. He applies his understanding to what he knows within the South African context.

And in response to Fanon’s diagnosis, Biko notes the condition and prescribes the remedy to cure these social and historical ills:

“We must reject the attempts by the powers that be to project an arrested image of our culture. This is not the sum total of our culture. They have deliberately arrested our culture at the tribal stage to perpetuate the myth that African people were near cannibals, had no real ambitions in life, and were preoccupied with sex and drink. In fact the wide-spread of vice often found in the African townships is a result of the interference of the white man in the natural evolution of the true native culture.”

Thus for Biko, his emphasis is on Black people and restoring to Black people a sense of the great stress they placed on the value of human relationships to illustrate that they always had a high regard of people; their property and life.

The reclamation and restoration of these values are central to the Black Consciousness Philosophy.

The call for Blacks to lead the struggle against apartheid is a dominant theme. According to Biko, no one can free Black people except Black people themselves.

He identifies the strength of the white power structure and sets it out, “The overall success of the white power structure has been in managing to bind the white’s together in defence of the status quo”.

Therefore, Biko aims to bind Black people together and create a unified liberation movement which uses its group dynamics to challenge the hegemony and status quo.

He also draws inspiration from the long liberation history of South Africa and its revolutionaries and touches on it in the article above.

This history goes back to the two great Xhosa chiefs, Ngqika and Ndlambe, and their respective prophet-intellectuals, Ntsikana and Nxele, in the 19th century.

This tradition also includes Tiyo Soga and Robert Sobukwe; the latter led the breakaway from the ANC to found the PAC because the ANC fraternised with white liberals and communists.

The Black Consciousness Movement uses the template built by the PAC to exclude white liberals from its midst to form a liberation movement led by Blacks.

At the time, most of the liberation movements were led by white liberals who financed them too. Very few Black organisations were not under white direction or guardianship.

The PAC broke this monopoly of white guardianship in the fifties, therefore, sowing the seeds for the BCM. The PAC was active in King Williams Town and Biko’s older brother, Khaya, was a member.

Biko also held Sobukwe in great esteem: he affectionately referred to him as The Prof. So Biko would have been very aware of their modus operandi because his brother tried on numerous occasions but without success to persuade him to join the PAC.

Biko’s article illustrated below, The Church as Seen by a Young Layman, which is available via the link as a PDF, illustrates Biko’s awareness of his history and the heroes that formed part of that long liberation struggle lineage.

In this article, he is concerned with the “return to our beliefs, values” and rewriting history to restore it with its original value.

He is also questioning the role the church plays in the subjugation of Black people and providing solutions to make it relevant to the oppressed in South Africa.

Biko’s awareness of the distortion of history by the settlers convinces him to reclaim it and restore it with its true value.

He explains that the coming to consciousness of the Black man will only be possible through rewriting Black history and producing in it the heroes that form the core of Black resistance to the white invaders. He writes:

“More has to be revealed, and stress laid on the successful nation-building attempts of men such as Shaka, Moshoeshe and Hintsa. These areas call for intense research to provide some sorely-needed missing links. We would be too naïve to expect our conquerors to write unbiased histories about us but we have to destroy the myth that our history starts in 1652, the year Van Riebeeck landed at the Cape.”

“Our culture must be defined in concrete terms. We must relate the past to the present and demonstrate a historical evolution of the modern black man,” he elaborates further.

His quest is not to return to some primordial or glorious past, but to return to it in spirit and seek inspiration from that history to make it relevant to the present.

Restoration of Black people’s history, beliefs and values is a recurring theme at the heart of the Black Consciousness Philosophy.

Philosophy is the academic study of knowledge, thought, and the study of life. It also includes any system of beliefs or values, or a personal outlook or viewpoint.

Originally, philosophy comes from the Greek word philosophia which means love of wisdom. The latter phrase encapsulates Steve Bantu Biko.

I Write What I Like captures and reflects Biko’s philosophia quality. His love of knowledge and wisdom permeate the text. It is a direct result of his study of life in South Africa, Africa and what is happening globally, plus his voracious reading.

He absorbs it all and uses his understanding to mould a philosophy that addresses the subjugation of Blacks in apartheid South Africa by demystifying the myths, systems or beliefs used to justify the oppression of Africans.

He gives the people a revolutionary outlook that breathes new life into them and the confidence to face the system as re-born men and women.

He never writes to boast or show-off. His intention is to change the thinking of Africans. He is committed to engaging with the ordinary person.

He wants to be understood. This is reflected in a response he gives to an interviewer in Our Strategy for Liberation.

“We believe it is the duty of the vanguard political movement which brings change to educate people’s outlook”, he explains.

The teacher, the educator, in him is obvious. The lucid exposition of the Black Consciousness Philosophy in the book speaks for itself.

These articles appeared in the SASO newsletter which was the theoretical organ of the Black Consciousness Movement; it was the medium used to disseminate ideas and educate its adherents and the wider society.

The readers of the newsletter, or readers of this book, who wish to explore and understand Black Consciousness will be enlightened by Biko’s articulate arguments, intelligence, touched by his humanity and impressed by his lack of vengeance against whites.

Despite his experiences with the apartheid police and subjugation by the regime, Biko is not bitter. This text lacks bitterness. The pronoun “I” is almost absent: it is synonymous with the ego. He maintains an objective perspective which indicates a sense of fairness.

I guess this is what Biko refers to as “The great powers of the world may have done wonders in giving the world an industrial and military look, but the great gift still has to come from Africa – giving the world a more human face”.

He retains that rare humane trait exhibited by philosopher kings or prophet intellectuals. He transcends the vanity created by the apartheid regime and its dehumanisation of the indigenous people.

Biko’s Black Consciousness Philosophy is revolutionary. It is the first time that a leader in South Africa articulates a liberation ideology or philosophy that addresses the psychological emancipation of the people.

Most leaders merely concentrated on the external factors such as unjust laws, toyi toying, violent struggle, sabotage, etc. Biko digs deeper than the skin and addresses the mind.

Therefore, he has a hard sell because his ideas are new. At the time he is writing, the ANC and PAC are banned so the Black Consciousness Movement is the vanguard movement leading the revolution in the absence of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe and Nelson Mandela and other elders.

Biko understands the importance of putting ideas across to the people in a language that they understand as he says in his own words, “All these must be explained to the people by the vanguard movement which is leading the revolution”.

As the vanguard movement, and the spiritual father of the movement, this burden falls on Biko’s young shoulders.

Unlike other leading intellectuals or those who use their intellectual powers of persuasion to uphold the status quo, and cloud their message through the use of abstract terms, or the language of academia to make their work accessible to the privileged minority, Biko writes in a simple, concise, precise and fluid manner.

Biko believes that ‘”Black Consciousness” seeks to talk to the black man in a language that is his own’. Therefore, he keeps his writing accessible to the audience he is addressing.

During the BPC/ SASO trial he explains that they settled for English as the common language because there were ten languages available and they had to cater for other groups like the Coloureds and Indians who fall under the definition of Black people according to the Black Consciousness Philosophy.

They are more or less equally oppressed and exploited; therefore, Black is not a term that refers to one’s skin colour. Rather it addresses the conditions of the oppressed and exploited.

He also elaborates how language is used and received by people from different cultures because of our different ways of reading or interpreting the context and contents of a speech.

For example, in response to a question about a document circulated at the funeral of an activist which the court believes the language can be interpreted as inciting violence or anger, Biko replies:

“I am saying both the drawers of this particular piece and the recipients will have no doubt about their communication. You in the middle who is an Englishman, who looks at words you know piecemeal, you may have problems, but the person who perceives it within the crowd has no problem. They are at one, they understand what they are talking about. You may not understand it because you are looking at the precise meaning of words.”

The text of Biko’s work is very simple and accessible. Because it is accessible, it is persuasive especially to people who understand the apartheid context and the historical period.

The longevity of I Write What I Like bears testament to its persuasiveness and relevance decades after it was published.

That he writes so simply and persuasively reflects his clarity of mind, his ideas and his ability to communicate complex ideas at the level of a layman to a layman without watering down the strength of the argument.

His clarity of thought is a hallmark of a philosopher. He is not interested in the abstract ideas numerous philosophers pursue.

Biko’s philosophy is rooted in his social and political context. It tackles the realities of the oppressed and creates a fighting philosophy in the process.

While reading Biko’s work, we take a number of things for granted. Firstly, we forget that he was only 23 years when he began to develop his own ideas and thinking about Black Consciousness.

Not many people at that age have such a clear conception of society or the world to start formulating such strong ideas. This is partly what makes I Write What I Like a remarkable work.

To say he did it alone is untrue. He worked with friends like Barney Pityana and other fellow students. Together they formed an intellectual cell where they debated and discussed issues and exchanged ideas.

Out of that cell emerged the Black Consciousness Movement. Its genesis and development follows similar lines of social change and revolutionary intellectual movements throughout the history of the world.

In addition, I alluded to how Steve was a lover of wisdom. Barney Pityana testifies that “Steve was a voracious reader. He read everything he could lay his hands on”.

Steve was a medical student but he could debate the finer points of literary criticism with Barney who was an English major.

His voracious reading expanded his intellectual horizons and allowed him to engage proficiently and intelligently with numerous disciplines such as philosophy, sociology, psychology, religion, history, politics, current affairs, etc.

That he was widely read, is evident in his comfort and ability to discuss different subjects, quote from myriad sources or bring together an amalgamation of ideas and apply them to the South African context and mould them into Black Consciousness.

We take our access to books, research papers, historical documents and the internet for granted. Biko didn’t have the resources modern scholars have today.

However, his voracious reading of what he could lay his hands helped him forge an international perspective and ideas that were universal in their appeal.

He was an astute observer of the events unfolding in the world such as the politics of decolonisation of Africa and India and the African Diaspora.

He was well versed in the local South African history and the resistance the locals put up against the British and Dutch settlers. All these various struggles that preceded him informed his ideas and helped to shape his philosophy.

The politics of the Civil Rights Movement in the US was also crucial to his learning and developing certain tenets of the Black Consciousness Philosophy.

This is evident in Chapter 14 entitled Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity.

He despairs at the role Christianity plays in the subjugation of Black people and calls for its reformation borrowing ideas from Black Theology and modifying them to suit the South African context.

Black theology is historically an American product emerging from the Black situation there. I’ll take the liberty to inflict a long quote on you from the article named above to illustrate my point.

“Here then we have the case for Black Theology. While not wishing to discuss Black Theology at length, let it suffice to say that it seeks to relate God and Christ once more to the black man and his daily problems. It wants to describe Christ as a fighting God, not a passive God who allows a lie to go unchallenged. It grapples with existential problems and does not claim to be an ideology of absolutes. It seeks to bring back God to the black man and to the truth and reality of his situation. This is an important aspect of Black Consciousness, for quite a large proportion of black people in South Africa are Christians still swimming in a mire of confusion – the aftermath of the missionary approach. It is the duty of all black priests and ministers of religion to save Christianity by adopting Black Theology’s approach and thereby once more uniting the black man with his God.”

What emerges from Biko’s series of articles is a solid philosophy inspired by diverse intellectual forces such as the African Nationalism of Jomo Kenyatta, Kenneth Kaunda, Kamuzu Hastings Banda and Julius Nyerere; the Pan Africanism of Kwame Nkrumah and Sekou Toure; the Negritude writers of West Africa and Paris, and the Black Power Movement of Stokely Carmichael a.k.a. Kwame Ture, Malcolm X, and the Black Panther Party.

There are very few surviving audio or video recordings of Steve Biko. He never got the opportunity to pen his own memoirs or autobiography to tell his own story.

However, a lot has been written about him. There are numerous articles, essays and books about him or his work, critiquing it.

Songs have been made about him. Documentaries and films too. All these individual narratives are like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that build a composite picture of the man, the legend, the tragic hero and the revolutionary.

They aid us in understanding how the world embraced him and what he represented. They illustrate the internationalist appeal of his work and the peoples it touched. Furthermore, they reinforce his enduring legacy.

There are those who accused him of racism. However, that is the propaganda used by those who feared or misunderstood his radical thinking and attempted to use that to demonise or discredit him.

Others who used that approach tried to undermine his legitimate concerns by attempting to portray him as a racist were the secret police and the state to undermine his message and uphold the status quo.

The text speaks for itself. It doesn’t call for annihilation of white people. It doesn’t call for revenge. Rather Biko preaches non-violence.

He preaches understanding. He addresses the concerns of those who claimed Blacks were racists. He made it clear:

“What of the claim that blacks are becoming racists? This is a favourite pastime of frustrated liberals who feel their trusteeship ground being washed off from under their feet. These self-appointed trustees of black interests boast of years in the experience in their fight for the ‘rights of the blacks’. They have been doing things for blacks, on behalf of blacks, and because of blacks. When the blacks announce that the time has come for them to do things for themselves all white liberals shout blue murder… What blacks are doing is merely to respond to a situation in which they find themselves the objects of white racism. We are in a position in which we are because of our skin. We are collectively segregated against – what can be more logical than for us to respond as a group?”

Biko explains why they chose to go at it as Blacks only. The definition of Blacks is not a matter of pigmentation or a lack of it but a mental attitude of declaring oneself as Black.

It is an inclusive term including oppressed groups such as the Coloureds (otherwise referred to as mixed race in other countries) and Indians.

These three groups were often referred to as non-white in South Africa and used as buffer layers between Blacks and whites but Biko and the BCM rejected that classification because it treated them as an inferior subspecies or subhuman of what was considered the norm – white.

He writes in The Definition of Black Consciousness, “We have in our policy manifesto defined blacks as those who are by law or tradition politically, economically and socially discriminated as a group in the South African society and identifying themselves as a unit in the struggle towards the realisation of their aspirations”.

“Merely be defining yourself as black you have started on a road towards emancipation, you have committed yourself to fight against all forces that seek to use your blackness as a stamp that marks you out as a subservient being”, he goes on to state.

This definition is both political and strategic to build up a powerful alliance between oppressed and exploited groups.

I Write What I Like is one of the few documents that preserves Biko’s voice and philosophy. We are grateful because it is the closest we can get to his own thinking without the use of an intermediary.

Nothing is lost in translation or interpretation. The text remains unaltered except for the brief paragraphs at the beginning of each chapter that provide a basic commentary putting the articles into context.

The book captures Biko’s thinking from the start of his political career and takes us up to within months of his death.

It provides us with insight into the evolution of the BCM from a small students union [SASO] through to its transformation into a fully fledged movement with various organisations linked to it such as the BPC.

It also illustrates the gradual evolution in Biko’s thinking from his modest start, speaking as the voice of Black students to his role as a leading statesman, representing the masses and setting out his vision for the future.

During the formation of SASO in Chapters 1 – 3, Biko and co refer to themselves as non-whites. However, in chapter 4, the word is obliterated from their vocabulary or conscience. It is nonexistent. From then on they refer to themselves as Black.

The text sets out the definition of Black Consciousness philosophy. Biko defines it as:

“Black Consciousness is in essence the realisation by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their operation – the blackness of their skin – and to operate as group in order to rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude. It seeks to demonstrate the lie that black is an aberration from the “normal” which is white. It is a manifestation of a new realisation that by seeking to run away from themselves and to emulate the white man, blacks are insulting the intelligence of whoever created them black. Black Consciousness therefore, takes cognizance of the deliberateness of God’s plan in creating black people black. It seeks to infuse the black community with a new-found pride in themselves, their efforts, their value systems, their religion and their outlook to life.”

This is precisely what Black Consciousness is about. It is about self determination. It rejects the idea that the lives and fate of black people can be defined by a tiny settler minority.

It is about reaffirming and reclaiming the Black system of beliefs and values, allowing Black people to assert their own personal outlook or viewpoint without coercion or persuasion by others i.e. the white man.

There are many ways of “being”. There are many ways of seeing the world. There are many ways of relating to the world. None is more superior or inferior than the other.

The intention is not to subjugate white people. In fact, it is to free them because they are also enslaved by their racism.

Biko argues that the system of apartheid was created specifically for the purpose of subjugation of Black people to exploit them and entrench their privileged position in society and benefiting from the riches of the country.

He believes it is not a coincidence Black people are exploited. It is a deliberate plan.

Therefore, Black Consciousness is Biko’s vehicle to liberation as he explains, “Liberation is therefore of paramount importance in the concept of Black Consciousness, for we cannot be conscious of ourselves and yet remain in bondage. We want to attain the envisioned self which is a free self”.

Biko opposes racism. His whole text is absent of racial incite. Rather he illustrates the pitfalls of racism and the harm it inflicts on both the racist and the victim. They are both enslaved by it.

His understanding of racism fundamentally echoes that of Frantz Fanon and American Black Power activists like Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton in the 1960s.

Carmichael and Hamilton defined racism as, “the predication of decisions and policies on considerations of race for the purposes of subordinating a racial group and maintaining control over that group”.

This form of institutional racism was further developed and explained by American sociologists like Robert Blauner. He argued, racism was “located in the actual existence of domination and hierarchy”.

Biko believes racism is a question of power, the power to subjugate and without that power one can’t be racist.

He defines racism as “discrimination by one group against another for the purpose of subjugation or maintaining subjugation”.

“We do not have the power to subjugate anyone… Racism does not only imply exclusion of one race by another – it always presupposes that the exclusion is for the purposes of subjugation”, he adds.

The definition of racism above illustrates that exclusion of whites from the Black Consciousness Movement is not an act of racism. There is no intent to subjugate or maintain subjugation. Therefore, it is not racist.

It is merely an act of solidarity among the oppressed to rid themselves of the shackles that enslave them. It is a genuine attempt to facilitate a very strong grassroots build-up of black consciousness such that Blacks can learn to assert themselves and stake their rightful claim.

Biko’s references to whites as the group that “wields power”, the “totality of white power”, or “white power presents itself as a totality” reinforces the idea that within that context, only whites can be racist because they wield all the power to subjugate, dominate and maintain the white supremacy structure to exploit Black people for their economic benefit.

Biko’s views are supported by Hendrik Vervoerd, the chief architect of apartheid. In his attempt to justify apartheid or separate development Vervoerd stated:

‘Reduced to its simplest form the problem is nothing else than this: We want to keep South Africa white… “keeping it white” can only mean one thing, namely white domination, not “leadership,” not guidance, but control, supremacy. If we agreed that is the desire of the people that the white man should be able to protect himself by retaining White domination, we say that it can be achieved by separate development.’

This is what Biko is rejecting and resisting. This is what he is fighting. This is the totality of white power he is against not the individual.

Furthermore, Biko not only objects to the white liberals trying to hijack the liberation movement, but to their paternalism in constantly treating Blacks like perpetual under 16s, and supplying them with solutions which suit the white liberals but are not what Blacks necessarily envision.

Like Carmichael and Hamilton, Biko dismisses the integration the liberals eschew because it is artificial. According to him, the integration they talk about is a response to a conscious manoeuvre rather than to the dictates of the inner soul.

Biko accepts an integration that is organic, mutual. He believes each group must be able to attain its style of existence without encroaching on or being thwarted by another.

Out of this mutual respect for each other and complete freedom of self-determination there will obviously arise a genuine fusion of the life-styles of the various groups.

He also rejects Black leaders who cooperate with the apartheid regime. He articulates the damage these so-called leaders inflict on the people through fragmentation of the struggle and the confusion they sow in the article entitled Let’s talk about Bantustans.

Bantustans, or Bantu homelands, were independent or autonomous African homelands set aside by the regime for different tribes or ethnic groups.

Biko was working hard to unite the people so he viewed the Bantustans as a South African version of the Roman imperialist idea of “Divide and Rule”.

The bantustans allocated 13% of the land to Africans who formed 80% of the population and left whites who were the minority, 20% of the population to enjoy 87% of the best arable land.

Therefore, Biko saw bantustan leaders such as Kaiser Mantanzima, leader of the Transkei, Gatsha Buthelezi of Zululand and Lucas Mangope of Bophuthatswana as “sell-outs and Uncle Toms”.

It is probably the only time one can detect some anger in Biko. He rips into the leaders and exposes the futility of their plans by allowing the people who are oppressing them to offer solutions to the problems they created.

Biko uses the following analogy to illustrate the futility of the apartheid regime prescribing solutions for the Bantustan leaders: “If you want to fight your enemy you do not accept from him the unloaded of his two guns and then challenge him to a duel”.

Biko’s disappointment with their approach is obvious. He doesn’t hide his strong views as illustrated: “there is no way of stopping fools from dedicating themselves to a useless cause”.

He is against the idea of these homelands. He sees them as a great injustice inflicted on the Blacks regardless of the propaganda the regime spins to make them look like there is genuine progress. Biko denounces them in the strongest terms.

‘These tribal cocoons called “homelands” are nothing else but sophisticated concentration camps where black people are allowed to “suffer peacefully”. Black people must constantly pressurise the bantustan leaders to pull out of the cul-de-sac that has been created for us by the system,” he writes.

He accuses these leaders of subconsciously aiding and abetting in the total subjugation of the country. They are exonerating the country and giving the process legitimacy.

“No, black people must refuse to be pawns in a white man’s game,” Biko warns the people.

He advocates for Black people to provide their own initiative and to act at their own pace and not one created for them by the system.

Apart from these leaders who are helping maintain the status quo, confusing the masses and fragmenting the resistance to apartheid, Biko rejects Black policemen, security forces or those who collaborate with them.

He sees them as “extensions of the enemy into our ranks”. He views them as a danger to the community and he is not afraid of stating that publicly. He doesn’t even see them as Black.

He doesn’t support them or their motives. They might as well be outsiders or Judas Iscariot to Biko:

“One can say of course that blacks too are to blame for allowing the situation to exist. Or to drive the point even further, one may point that there are black policemen and black special branch agents. To take the last point first, I must state categorically that there is no such thing as a black policeman. Any black man who props the system up actively has lost the right to being considered part of the black world: he has sold his soul for 30 pieces of silver and finds that he is in fact not acceptable to the white society he sought to join. These are colourless white lackeys who live in a marginal world of unhappiness. They are extensions of the enemy into our ranks.”

He demonstrates this fearlessness at the SASO/ BPC Trial in 1976. In response to a question by the defence attorney about black policemen who work for the government, Biko calls them “traitors”.

He says this without any equivocation and he says this to a room-full of policemen. One has to remember that the apartheid police was one of the most feared institutions in the country then.

They can arrest people without any charges and detain them. They kill with impunity because they have guaranteed state immunity. They beat people and they have no recourse to justice.

“The black man has no ill-intentions for the white man. The black man is only incensed at the white man to the extent that he wants to entrench himself in a position of power to exploit the black man.”

Steve Bantu Biko

I Write What I Like

The two chapters that cover the SASO/ BPC Trial are enlightening. The transcripts illustrate how Biko uses the trial as a platform to spread Black Consciousness. He transforms the charge of terrorism against the state itself.

He walks a fine line between walking and talking revolution and inciting treason which can earn him a jail or death sentence.

Not only does he defend Black Consciousness, but he addresses white misconceptions of Black Consciousness.

He reinforces the movements commitment to non violence, anti-racism, anti-exploitation, unity and creation of an egalitarian society which Biko seeks to create.

The trial was a result of members of the BPC holding a pro Frelimo Rally to celebrate Frelimo as the de facto government of Mozambique.

However, the way the indictment is formulated, makes it clear that Black Consciousness is on trial.

Biko turns it around. This trial is for the Black Consciousness Movement what the Treason Trial was for the Congress Alliance of the 1950s. It is to Biko what the Rivonia Trial [1964] was for Mandela.

Both these trials showcase the fearlessness of the leadership and the content of the message that both trials send out to the Black community and the world at large.

The SASO/ BPC Trial confirms to society and the world that Biko is the authentic voice of the people and he is not afraid to say openly what other Blacks think but are too frightened to say it aloud.

The trial also illustrates how Biko handled hostile interrogation or cross examination by being always quick to take the route of humour and respond to what was human in his persecutors as illustrated in this short exchange.

QUESTIONER: Why do you seek confrontation?

BIKO: There is nothing wrong with confrontation as such.

QUESTIONER: Confrontation leads to violence. Do you approve of violence?

BIKO: No, confrontation does not necessarily leads to violence. You and I are now in confrontation, and there is no violence.

ADVOCATE ASIDE TO COLLEAGUE: This isn’t a confrontation – it’s a massacre.

Black people though remain his main concern. The whole philosophy of Black Consciousness is the remedy Biko believes will cure the patient and rejuvenate them back into health.

He turns his attention to them in We Blacks. Biko was a medical student and at times uses medical terms to scrutinise the problem.

Black Consciousness therefore is his way of diagnosing the ailment, establishing the root cause and setting up the remedy as he puts it in his own words:

‘One needs to understand the basics before setting up a remedy. A number of organisations now currently “fighting apartheid” are working on an oversimplified premise. They have taken a brief look at what is, and have diagnosed the problem incorrectly. They have almost forgotten about the side effects and have not even considered the root cause. Hence whatever is improvised as a remedy will hardly cure the condition.’

By this, Biko means that other organisations ignore the premise that apartheid is tied up with white supremacy, capitalist exploitation and deliberate oppression so it makes the problem more complex.

He also notes that spiritual poverty is also part of the cocktail of social ills that creates mountains of obstacles in the course of emancipation of Black people.

Biko asks probing questions of the Black man. “What makes the black man fail to tick? Is he convinced of his own accord of his own inabilities? Does he lack in his genetic make-up that rare quality that makes a man willing to die for the realisation of his aspirations? Or is he simply a defeated person?”

He answers these questions and articulates them well. Like a doctor, and Fanon his inspiration who also studied medicine [psychology], he understands the effects of apartheid and colonialism.

He understands how they dehumanise the native and mess up his head and self confidence.

In characteristic style, Biko proclaims: ‘The first step therefore is to make the black man come to himself; to pump back life into his empty shell; to infuse him with pride and dignity, to remind him of his complicity in the crime of allowing himself to be misused and therefore letting evil reign supreme in the country of his birth. This is what we mean by an inward-looking process. This is the definition of “Black Consciousness”‘.

The seeds of the Black Consciousness Philosophy speak for themselves when in 1976, school children reject Afrikaans as a medium of instruction and take to the streets in protest.

The apartheid police retaliates by shooting them down in a hail of bullets on the streets of Soweto. These school children answer Biko’s question about the Black man:

“Does he lack in his genetic make-up that rare quality that makes a man willing to die for the realisation of his aspirations? Or is he simply a defeated person?”

No! They are not defeated people. They have that rare quality that makes a man or woman or child willing to die for the realisation of his or her aspirations.

The Black Consciousness Philosophy and Movement produce new men and women.

They are conscious. They are militant. They are proud of their blackness and totally reject the white yardstick as the standard to judge themselves. They are prepared to die for their ideals.

Biko’s realisation comes to bear fruit. His aim to remove the fear factor in Black people is evident.

He states, “But part of what you are trying to kill has not quite died, the whole concept of fear, and black people steeped in fear. We want to get them away from this”.

The children are not the only ones who are prepared to die. Many members of the Black Consciousness Movement are hunted down and murdered by the apartheid regime too.

Some are murdered while they are being held by the police. Biko is one of them and the most high profile of the lot.

He believes in his ideas and dies for them. He dies for his conviction: “It is better to die for an idea that will live than to live for an idea that will die”.

He also knows that the cause is justified and victory is assured as he prophesies, “We believe in the righteousness of our strength, that we are going to get to the eventual accommodation of our interests within the country”.

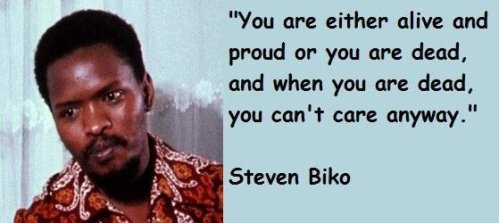

In the final chapter, On Death, Biko relates how a friend of his is killed days before he is arrested for the final time, “They just killed somebody in jail – a friend of mine – about ten days before I was arrested”.

He talks about death casually in an almost detached manner, like a man who is used to death. He talks about it like a man who has reconciled himself with death.

The irony is this final chapter contains the last words recorded shortly before his death.

Like many of his comrades and school children murdered by the regime, he also answers his own question when the regime murders him: “Does he lack in his genetic make-up that rare quality that makes a man willing to die for the realisation of his aspirations? Or is he simply a defeated person?”

The opening paragraph of the last chapter illustrates that rare quality in his genetic make-up that makes a man willing to die for the realisation of his aspirations.

This paragraph I am about to quote is quite poignant. It is ironic because months later he is murdered and his words ring true.

“You are either alive and proud or you are dead, and when you are dead, you can’t care anyway. And your method of death can itself be a politicising thing. So you die in the riots. For a hell a lot of them, in fact, there’s nothing really to lose – almost literally, given the kind of situations that they come from. So if you can overcome the personal fear of death, which is a highly irrational thing, you know, then you’re on your way.”

Again Biko is correct. His death, the method of his death is a “politicising thing”. His death shows up the brutality of the apartheid regime. The world’s eyes focus on the regime and the opposition to apartheid outside the borders of South Africa increases.

Unfortunately, he is wrong in one aspect. There is something to lose.

The BCM loses its most articulate theorist, it’s charismatic ambassador and selfless spiritual leader. South Africa loses a young statesmen who could have gone on to become an influential leader in post apartheid South Africa.

South Africa loses a visionary who wanted to build a new society as he said: “in our country there shall be no minority, there shall be no majority, just the people. And those people will have the same status before the law and they will have the same political rights before the law. So in a sense it will be a completely non-racial egalitarian society”.

His words, his ideas are the spark that light a veld fire across South Africa. With his simple messages Black is Beautiful! Be proud of your Blackness! Assert yourselves and be self reliant!

“The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” Organise! His work is complete. Black people shed their feeling of inferiority and they walk tall.

Biko’s writing is sincere and thought provoking. You might not agree with everything he says partially because time and circumstances have changed and there have been material changes in South Africa.

However, that is not entirely true. Biko warns about the dangers of the integration that the white liberals are pushing for. He warns them that it is bound to be a disaster if it is not done properly:

This is the white man’s integration – an integration based on exploitative values. It is an integration in which black will compete with black, using each other as rungs up a step ladder leading them to white values. It is an integration in which the black man will have to prove himself in terms of these values before meriting acceptance and ultimate assimilation, and in which the poor will grow poorer and the rich richer in a country where the poor have always been black. These are concepts which the Black Consciousness approach wishes to eradicate from the black man’s mind before our society is driven to chaos by irresponsible people from Coca-cola and hamburger cultural backgrounds.

Biko is correct. The poor in South Africa today are growing poorer and the rich richer due to the lack of transformation Biko proposes in I Write What I Like.

Recent reports in the media have highlighted how people are going for days without food to eat because of the high unemployment and lack of structural changes.

The changing of political power from white leaders to black leaders did nothing economically for Black people.

Biko expresses his concerns if this happens:

There is no running away from the fact that now in South Africa there is such an ill distribution of wealth that any form of political freedom which does not touch on the proper distribution of wealth will be meaningless. The whites have locked up within a small minority of themselves the greater proportion of the country’s wealth. If we have a mere change of face of those in governing positions what is likely to happen is that black people will continue to be poor, and you will see a few blacks filtering through into the so-called bourgeoisie. Our society will be run almost as of yesterday. So for meaningful change to appear there needs to be an attempt at reorganising the whole economic pattern and economic policies within this country.

Of course, he is correct on that point. This is the situation in South Africa today.

The rise of the technocrats and Big Chief Syndrome has created a class of the ruling elite and their acolytes who benefit from the country’s vast economic resources while the poor are sidelined.

As a matter of fact, the great compromise made by Mandela benefitted foreign capital and their compradors. Imperialism triumphed at the expense of the people’s revolution, betraying the ANC Freedom Charter.

Under the current leadership there is no distinction between public authority and private interests. Corruption has become endemic and striking workers are shot down or dispersed with brutal force, something reminiscent of the apartheid regime.

Biko’s words, ideas and philosophy still appeal to the poor and downtrodden who still see him as a symbol of resistance and liberation against Black exploitation and oppression.

Today there are those like the Economic Freedom Fighters and others who claim validity for their ideas by claiming a lineage to Biko.

They are calling for genuine economic transformation and are seeking to address the land question which has seen the majority of the land remaining in the hands of a tiny minority.

Steve Bantu Biko and the Black Consciousness Philosophy remain relevant to our generation because of the lack of reorganisation of the whole economic pattern and economic realities in Africa.

He remains a politicising factor today because Black people remain at the bottom rung of every society we live in.

Biko’s calls for Black people to unite and liberate themselves are relevant today when we see what is happening with police brutality and militarisation of the security forces within Africa and America.

Black lives don’t matter is the message they seem to be sending out.

However, Black Consciousness urges us to assert ourselves: Be proud of your Blackness!

His writing displays the many facets that are Steve Biko. Chapter 17, American Policy towards Azania, showcases Biko at his diplomatic best. It is a masterclass in diplomacy.

He walks a fine line between telling the greatest superpower off and pricking their conscience: he comes as close he legally can to call for trade boycotts, arms embargoes, and withdrawal of investments from Senator Dick Clark.

Steve wrote the memorandum after he was released from 101 days in detention under section 6 of the Terrorism Act less than a week before his meeting with Clark.

He had no access to books, newspapers, the radio while he was held in isolation. He only had access to a Bible. The coolness and tact he displays in the memorandum illustrates Biko speaking with a mature and conscious authority as leader of the real opposition to the Nationalists in Pretoria.

He makes a passionate and penultimate plea to those who can bring about a nonviolent end to the tyranny of apartheid. The only reason apartheid continued for so long is because America supported this totalitarian regime.

America has a long history of supporting dictators, totalitarian regimes and masterminding coups in Africa and South America, Israel and Asia.

Biko picks that thread up and informs Senator Clark:

“Because of her bad record America is a poor second to Russia when it comes to choice of an ally in spite of black opposition to any form of domination by a foreign power. Heavy investments in the South African economy, bilateral trade with South Africa, cultural exchanges in the fields of sport and music and of late joint political ventures with the Vorster-Kissinger exercise are amongst the sins with which America is accused. All these activities relate to whites and their interests and serve to entrench the position of the minority regime”.

This is a different Biko speaking from the Biko who we meet during the formation of SASO. This Biko now speaks with the an air of diplomacy and statesman-like air.

He also sets out minimum requirements he expects the Americans to meet if America intends to act as a mediator because her current actions make her hands dirty and that is unacceptable for a mediator.

One of Biko’s requirements is that:

“America must call for the release of political prisoners and banned people like Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, Steve Biko, Govan Mbeki, Walter Sisulu, Barney Pityana and the integration of these people in the political process that shall shape things to come.”

It is also worth noting that in Chapter 18, Our Strategy for Liberation, Biko has come full circle. He expresses hopes for groups of whites who can come up to form coalitions with blacks to minimise the conflict.

It is a far cry from the initial strategy of withdrawal from Black-white coalitions of SASO and the Black Consciousness Movement’s formative years.

This is a reflection of the confidence Biko had in the Black Consciousness Movement’s ability to stand their ground and by their values and beliefs and to have a strong and leading voice within any Black-white coalitions.

It illustrates Biko’s ability to confront reality as he grapples with the issue of how to achieve freedom, and grow while developing his ideas all the time and broadening his outlook simultaneously.

I Write What I Like sets out the genesis, growth, development and evolution of the Black Consciousness Philosophy.

It is an engaging read showcasing the subtle evolution of Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement’s thinking and philosophy.

Biko had faith and conviction in victory. He took up a struggle alongside other men and women of his generation, and in doing so, managed to create a spark that powerfully resonated and disturbed the forces of injustice.

I don’t know if he knew that he was lighting fires of struggle throughout the world. However, I know that whenever his name is mentioned or his image appears, he still has the moral strength to powerfully disturb the forces of injustice today and inspire the oppressed and exploited to stand up for their rights.

His image and name still ignite a passion within the oppressed and exploited today that makes the foundations of power tremble. His conviction, humanity and demanding character command respect.

He was a revolutionary among revolutionaries. He was a man who could have gone on to be a successful doctor or lawyer, but he turned his back on the easy road, and dedicated himself to assert himself as a man of the people; a man who makes common cause with the suffering of others. That is probably what inspires people the most.

The apartheid regime killed Biko. It killed him because of its entrenched racism. Racism is a mental illness. It is also a question of power. Biko had diagnosed their condition and setout a remedy to cure their malady.

He also recognised their power. He knew that a unified Black people were the antidote to white power. Therefore, he was a threat to the white hegemonic power with his calls to unite Black people and confront the perpetrators of evil by creating a unified liberation movement.

Therefore, they killed him before he could heal them. They killed him before he seized power from them using the group dynamics.

Fortunately, you can’t kill ideas. Ideas do not die. And I Write What I Like contains the ideas, the seeds that Biko planted, and they are still germinating and bearing youths full of revolutionary fervour.

These are youths who are in search of the society Biko envisioned where there would be a reorganising of the “whole economic pattern and economic policies within this country” and probably within Africa, South America, Asia and the West.

This book contains Biko’s ideas that encourage the Black man and woman to have confidence in themselves and their abilities.

This book is above all about revolutionary conviction and faith in the cause and outcome, revolutionary conviction, revolutionary faith in what you are doing, and the conviction that victory belongs to us and that struggle is our only solution.

Biko lives! some say. His ideas are still alive. That’s why Biko, an embodiment of revolutionary ideas and self sacrifice is alive.

Young people thirsty for dignity, thirsty for courage, thirsty for Biko’s ideas and for the vitality he symobolised in South Africa and across the continent seek out to drink from the invigorating source represented by our revolutionary spiritual father.

His ideas inspire us and are inscribed in our hearts and minds. His ideas live in each of us in the daily struggle we wage and this is why this book remains relevant today as it was when it was first published in 1978.

I Write What I Like is a masterpiece of liberation and political philosophy focusing on Biko’s strengths bolstered by his love of writing.

He combines his love of the craft of writing and what he is passionate about – freedom and liberation and politics – and produces a historical document that will be read for generations to come.

And it will continue to inspire writers, bloggers, musicians, artists, scholars and activists and many others too numerous too mention.

Biko understands that “The most powerful weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed” and he puts pen to paper to decolonise the mind and shatter the shackles that bind the Black man and woman’s mind.

I Write What I Like is an enduring tribute to the depth and range of Steve Biko’s thoughts and ideas. His selfless reflections, thoughts, resilience, wit, wisdom and lasting faith in a humanely shared planet will influence Black Consciousness scholars, disciples and converts journey into the future, to create a better future where we can show the world a more human face.

This book is a collector’s item and a book you should at least read once in a lifetime. It is a worthwhile investment and every cent or penny you spend on it is worth it. I recommend it.

You can check out a PDF version of I Write What I Like at this link http://abahlali.org/files/Biko.pdf. However, I prefer the real book because there is nothing like holding it in your hands and engaging directly with it

I leave you with a quote from Steve Biko which best sums up his vision in this book and a phrase that appeared on the first page of the Daily Dispatch with a large colour portrait of Steve and the phrase on either side of it read:

“We salute a hero of the nation.”

[“Sikahlela indoda yamadoda.”]

“We have set on a quest for a true humanity, and somewhere on the distant horizon we can see the glittering prize. Let us march forth with courage and determination, drawing strength from our common plight and our brotherhood. In time we shall be in a position to bestow upon South Africa the greatest gift possible – a more human face.”

Steve Biko will live forever!

Thank you for sharing this..

Best Wishes

john

LikeLiked by 2 people

True John Flanagan. He lives forever. Thanks for taking the time to read and comment. I appreciate your feedback. All the best to you too. Have a great week.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: I WRITE WHAT I LIKE – STEVE BIKO 1946 – 1977: Book review, analysis and commentary | Christians Anonymous

Great post! Thank you for bringing to attention the life of this most extraordinary man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a pleasure brother. Thanks for the kind compliments. Indeed, more people need to understand and learn about this extraordinary man and the great things he did to turn around the fortunes of his country and the thinking of many Africans. Thanks again for reading this blog and taking the time to post a comment. One love.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Thank You | thegatvolblogger

Pingback: Afrophobia or xenophobia is an ugly thing: it is unAfrican! | thegatvolblogger

I truly love your blog.. Very nice colors & theme. Did you create this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my very own site and would like to learn where you got this from or what the theme is named. Appreciate it!

LikeLike

Hi, everything is provided by the WordPress CMS and you have numerous themes and layouts you can choose from.

LikeLike

Pingback: Arrest of Steve Bantu Biko: beginning of the end and martyrdom of a legacy | thegatvolblogger

It is better to die for an idea that will live than to live for an idea that will die”.

Thank you for sharing the story of a great man. This made my day

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks @Adan for thw kind compliments. It is pleasure to know that the article provided some sense of pleasure and that you were rewarded for reading this perspective on a great man. That also makes my day. Keep a look out for more. I have more coming up on Steve Biko. Blessed.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing about Steve Bantu Biko, I Write What I Like is a required reading on the my program SIT Study Abroad: Multiculturalism and Human Rights in Cape Town, The students all coming from North American Universities find Biko’s work powerful and life changing! I will certainly be pointing this blog to future students

LikeLike

Reblogged this on gloriakendiborona.

LikeLiked by 1 person

@gloriakendiborona thanks a lot. Much appreciated.

LikeLike